Keynote Addresses

Friday, October 10: “Setting Plato Straight: Translating Ancient Sexuality in the Renaissance”

Todd Reeser

Director, Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies (GSWS) Program

Professor of French and GSWS, University of Pittsburgh

http://www.frenchanditalian.pitt.edu/people/faculty/reeser

Abstract:

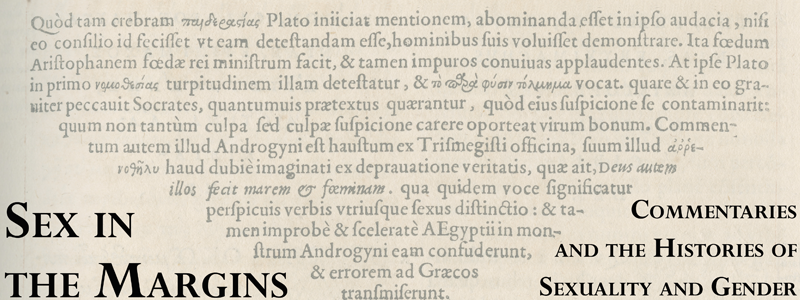

As fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Humanists read, digested, and translated Plato, they found themselves faced with a fundamental problem. On the one hand, the rebirth of the Ancients implied a “fidelity” to the words and the sense of Greek texts. On the other hand, many Humanists refused to translate faithfully, and thus to propagate, the institution of pederasty or the other homoerotic elements in the Platonic corpus. This recurring tension in Christian-Humanism could not be avoided because of the blatant homoerotics in Plato. In this talk, I present an overview of the critical questions around this tension, with a focus on translation and hermeneutics, in translations, commentaries, and literary texts from Italy, France, and Germany. This presentation is drawn from my book in press, a comparative and comprehensive study of the reception of Platonic sexuality from the first Renaissance translations of Plato’s erotic dialogues in the early fifteenth century (by Leonardo Bruni) to Michel de Montaigne’s skeptical commentary on translation in the late sixteenth century, with many stops in between.

Saturday, October 11: “The Commentator as ‘Erotomaniac’ and the Scholarly Commentator: Two Nineteenth Century Commentaries on Catullus”

Jennifer Ingleheart

Senior Lecturer in Classics, Durham University

https://www.dur.ac.uk/classics/staff/?id=1147

Abstract:

Commentaries reflect the concerns and preoccupations of those who write them (Nabokov 1962, Most 1999, Gibson/ Kraus 2002). This paper explores two nineteenth century commentaries on Catullus: the first by the Oxford don Robinson Ellis (1876, 18892), and the second the notes that accompany the 1894 translations of Catullus’ poems by Leonard Smithers, pornographer and (in the words of Oscar Wilde) “the most learned erotomaniac in Europe,” and Sir Richard Burton, who made pederasty his “special subject” after penning the “Terminal Essay” appended to his 1885-6 translation of the Arabian Nights. While Burton planned to annotate their translations “from an erotic (and especially a paederastic) point of view,” the project was cut short by Burton’s death, and Lady Isabel, Burton’s widow, expurgated words that she found unacceptable in Burton’s translation (according to Smithers). Nevertheless, sex is hardly in the margins either in the translations of Catullus or in the notes “explanatory and illustrative” that explicate them; the book as a whole offers an intriguing insight into the history of sexuality, not least because of the interests of its authors and the way in which their approach is in dialogue with those of more mainstream scholarly commentators. Ellis’ commentary is exemplary of such scholarly productions, yet, as Ralph Hexter argues in a forthcoming paper, Ellis may have been suspected of same-sex leanings, and this paper explores the ambiguities and evasions that are found in Ellis’ commentary as it deals with sexual subject matter and in particular, homoerotic topics.